I got the rear tire off the rim today in the ongoing '71 Bonneville project during a late March snowstorm. It had a Lien Shin tire on it. I'm unfamiliar with that brand and I can't find a heat pressed time stamp on it. Tires produced before the year 2000 use a 3 digit code that makes it difficult to determine which decade they were made in (first two digits are month of manufacture, last digit is the year). Tires after 2000 use a four digit code (week # of manufacture followed by a the last two digits of the year, ie: 0501 would be the fifth week of 2001). A 511 would be the 51st week (December) of a year ending in 1, ie: 1981, 1991.

While I couldn't find a stamped date on the Lien Shin tire, there is a three digit date stamp on the Inoue front tire: 511. Based on the bike's last sticker on the SATAN license plate ('84), this probably dates the front tire to the 51st week (December) of 1981. I was 12 when this tire was manufactured. I'm still amazed that it works at all and the inner tube holds pressure.

Taking a tire this old and stiff off was tricky, but as with the TIger tire change last year, a judicious application of heat really helps soften the rubber and makes removal easier, especially in the winter. It was -17°C outside so I put the shop heater next to the tire and let it warm up, then removing it with the irons was pretty easy.

Once I had the old rubber out of the way, I went at the rim with a wire brush and it cleaned off the surface rust well. Some SOS soap pads and then a bout with the pressure washer out in the snow storm and the rim came up nicely.

Next time I have some time and space I'll get the front tire removed and prep that too, then it'll be time to order some wheel hardware (bearings and brake pads). With the wheels rebuild, I'll clean up the frame and repaint it and then it's time to start putting the rolling chassis back together.

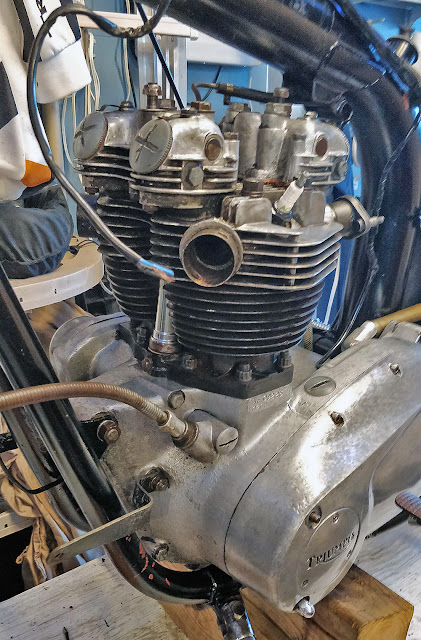

While I had the wheels off I took the rear brake apart. I keep being surprised by how simple this bike is. The rear brake is a mechanical mechanism, no hydraulics in sight. You press on that big brake lever (it's big because you need the mechanical advantage for it to work) and that pulls the rod connected to a spinner on the top of the rear brake drum. The drum spins and applies the brake. When you let go, a spring on the drum spinner disengages the brake. You must get pretty good feel out of a direct mechanical system like this, and you're not carrying any extra weight from a hydraulic system (fluid container, piston, pipes, caliper cylinders, etc), but I bet you've gotta have big calves to lock it up.

I'm back at work this week so it might be a few days before I take another swing at it, but it's exciting to get to the point where the bike is enough pieces that I can see how it'll go back together again.